Kenneth Bailey has spend four decades living in Egypt,

Lebanon, Israel, and Cyprus, most recently serving as professor of Middle

Eastern New Testament studies at Tantur Ecumenical Institute in Jerusalem. In

the early chapters of Jesus Through Middle Eastern Eyes, Bailey sheds understanding on some of the details in

the story of Christ’s birth as recorded in the Gospels.

[I]t is evident that

the story of the birth of Jesus (in Luke) is authentic to the geography and

history of the Holy Land. The text records that Mary and Joseph “went up” from

Nazareth to Bethlehem. Bethlehem is built on a ridge which is considerably

higher than Nazareth. Second, the title “City of David” was probably a local

name to which Luke adds “which is called Bethlehem” for the benefit of nonlocal

readers. Third, the text informs the reader that Joseph was “of the house and lineage of David.” In the Middle East, “the house of so-and-so” means “the

family of so-and-so.” Greek readers of this account could have visualized a

building when they read “house of David.” Luke may have added the term lineage to be sure his readers understood him. He

did not change the text, which was apparently already fixed in the tradition

when he received it (Lk 1:2). But he was free to add a few explanatory notes.

Fourth, Luke mentions that the child was wrapped with swaddling cloths. This

ancient custom is referred to in Ezekiel 16:4 and is still practiced among

village people in Syria and Palestine. Finally, a Davidic Christology surfaces

in the account. These five points emphasize that the story was composed by a

messianic Jew at a very early stage in the life of the church.

For the Western mind

the word manger invokes the words stable or barn. But in traditional Middle Eastern villages this is not the case. In

the parable of the rich fool (Lk 12:13-21) there is mention of “storehouses”

but not barns. People of great wealth would naturally have had separate

quarters for animals. But simple village homes in Palestine often had but two

rooms. One was exclusively for guests. That room could be attached to the end

of the house or be a “prophet’s chamber” on the roof, as in the story of Elijah

(1 Kings 17:19). The main room was a “family room” where the entire family

cooked, ate, slept and lived. The end of the room next to the door, was either

a few feet lower than the rest of the floor or blocked off with heavy timbers.

Each night into that designated area, the family cow, donkey and a few sheep

would be driven. And every morning those same animals were taken out and tied

up in the courtyard of the house. The animal stall would then be cleaned for

the day. Such simple homes can be traced from the time of David up to the

middle of the twentieth century. I have seen them both in Upper Galilee and in

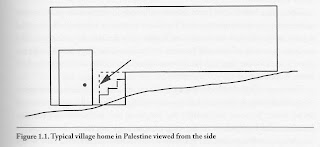

Bethlehem. Figure 1.1 illustrates such a house from the side.

The roof is flat and

can have a guest room built on it, or a guest room can be attached to the end

of the house. The door on the lower level serves as an entrance for people and

animals. The farmer wants the animals

in the house each night because they provide heat in winter and are safe from

theft.

The same house viewed

from above is illustrated in figure 1.2

The elongated circles

represent mangers dug out of the lower end of the living room. The “family

living room” has a slight slope in the direction of the animal stall, which

aids in sweeping and washing. Dirt and water naturally move downhill into the

space for the animals and can be swept out the door. If the family cow is

hungry during the night, she can stand up and eat from mangers cut out of the

floor of the living room. Mangers for sheep can be of wood and placed on the

floor of the lower level.

Source: Jesus Through Middle Eastern Eyes: Cultural

Studies in the Gospels by Kenneth E. Bailey (Downers Grove, IL:

InterVarsity Press; 2008) p. 28-30

This entry was posted

at Monday, December 12, 2011

and is filed under

Advent,

Bible,

Christian faith,

Scripture

. You can follow any responses to this entry through the

comments feed

.